Change Leadership: Point of View on Uncertainty and Ambiguity

There are many answers possible to the question "what is change management?". Some assume that change is something that is exclusively the responsibility of the Human Resources team. Others believe that good communication is synonymous with good change management. In reality, managing change requires diversified actions and the capacity to navigate uncertainty while engaging the whole organization system. Doing this well means different things in different surroundings.

Fundamentally, though, to manage change means to transform an organization from current state to future state using deliberate and effective practices for diagnosis, planning, structuring, delivering, sustaining, and measuring operational and organizational change, while motivating change stakeholders to come along the change journey and enable them to work through any resistance they may experience.

This definition is broad because it takes change delivery (project management) into account. The focus below, however, will be predominantly on the people-side of change.

Fundamentally, though, to manage change means to transform an organization from current state to future state using deliberate and effective practices for diagnosis, planning, structuring, delivering, sustaining, and measuring operational and organizational change, while motivating change stakeholders to come along the change journey and enable them to work through any resistance they may experience.

This definition is broad because it takes change delivery (project management) into account. The focus below, however, will be predominantly on the people-side of change.

|

Why do Organizations Need to Change?

We can differentiate change initiatives in an organization along their characteristics. For example: developing new products or services, implementing regulatory compliance, maintaining digital platforms, improving workforce engagement, unlocking cost and efficiency opportunities, completing merger integration or divestitures, and so on. |

The need for organizational change always originates in the external environment and mainly impacts processes, systems, and people inside the organization. When transforming an organization, it is therefore important to bring its personnel along on the change journey, since it is people who make organizations run (this is, of course, different when processes and systems were largely automated).

Most change efforts constitute a burning platform (e.g., regulatory action) or an opportunity to create a better future (e.g., expected profit increases). A burning platform can create an incentive for personnel to support the change given the potentially negative consequences of not changing. It is usually harder to convince people to support an opportunity-driven change when they believe that they stand to lose something as a consequence (more on resistance below).

Another helpful contrast is to think of organization change as transactional or transformational. Transactional change is typically gradual and targets work practices, structure, policies, procedures, climate, motivation, responsibilities, and skills of an organization's system. To sustain transformational change, a disruption needs to take place at the organization's core. This means to reshape external environment interactions, leadership practices, mission, strategy, or the organization's culture, and to adopt new norms, behaviors, and incentives. Transactional and transformational change are not mutually exclusive choices. Rather, a gravity-like effect is in place. Take, for example, an organization's mission (considered a transformational organizational component). Redefining the mission almost always impacts responsibilities and skills requirements (which are considered transactional components).

Worth noting: whether the change is a burning platform or an opportunity, illustrating its purpose will provide a north star for execution and communications. Simply announcing the desired outcome and laying out execution steps does not to motivate people sufficiently to support the change.

Most change efforts constitute a burning platform (e.g., regulatory action) or an opportunity to create a better future (e.g., expected profit increases). A burning platform can create an incentive for personnel to support the change given the potentially negative consequences of not changing. It is usually harder to convince people to support an opportunity-driven change when they believe that they stand to lose something as a consequence (more on resistance below).

Another helpful contrast is to think of organization change as transactional or transformational. Transactional change is typically gradual and targets work practices, structure, policies, procedures, climate, motivation, responsibilities, and skills of an organization's system. To sustain transformational change, a disruption needs to take place at the organization's core. This means to reshape external environment interactions, leadership practices, mission, strategy, or the organization's culture, and to adopt new norms, behaviors, and incentives. Transactional and transformational change are not mutually exclusive choices. Rather, a gravity-like effect is in place. Take, for example, an organization's mission (considered a transformational organizational component). Redefining the mission almost always impacts responsibilities and skills requirements (which are considered transactional components).

Worth noting: whether the change is a burning platform or an opportunity, illustrating its purpose will provide a north star for execution and communications. Simply announcing the desired outcome and laying out execution steps does not to motivate people sufficiently to support the change.

Change is Hard

It is occasionally alleged that 70% of change initiatives fail and that effective execution methods increase an organizations chances of success. A counterpoint to this argument is that there exists little supporting research. We can reason, however, that skills proficiency creates good results. Change management competencies are therefore a necessity in organizations.

Change is hard because it unsettles the status quo, creating uncertainty and ambiguity. Another dimension makes it even harder: whether they are for-profit or mission-driven, organizations are complex constructs. This complexity can further impede change. Consider, for example, the effort it takes to align on a project's objectives with cross-functional teams in a multi-national firm (which, most often, is helped with good leadership and governance). Compounding the effects of organizational complexity is the non-linear nature of change (taking two steps forward and one step back) and that projects cause competition for attention and resources. Hence, when not evolving is not an option for an enterprise, any progress will involve (some) struggle.

Little can be done about the fact that impactful change must be disruptive to the status quo. What effective change management strategies can accomplish is to help organizations and their personnel to work through the disruption in the best possible way, and to cope with complexity and non-linearity.

Signs of Change Being Difficult

It is possible to observe the symptoms of an organization's difficulties to transform itself:

When these issues lead to uneven change execution, the consequences can be serious:

It is occasionally alleged that 70% of change initiatives fail and that effective execution methods increase an organizations chances of success. A counterpoint to this argument is that there exists little supporting research. We can reason, however, that skills proficiency creates good results. Change management competencies are therefore a necessity in organizations.

Change is hard because it unsettles the status quo, creating uncertainty and ambiguity. Another dimension makes it even harder: whether they are for-profit or mission-driven, organizations are complex constructs. This complexity can further impede change. Consider, for example, the effort it takes to align on a project's objectives with cross-functional teams in a multi-national firm (which, most often, is helped with good leadership and governance). Compounding the effects of organizational complexity is the non-linear nature of change (taking two steps forward and one step back) and that projects cause competition for attention and resources. Hence, when not evolving is not an option for an enterprise, any progress will involve (some) struggle.

Little can be done about the fact that impactful change must be disruptive to the status quo. What effective change management strategies can accomplish is to help organizations and their personnel to work through the disruption in the best possible way, and to cope with complexity and non-linearity.

Signs of Change Being Difficult

It is possible to observe the symptoms of an organization's difficulties to transform itself:

- Stakeholders are not aligned on or committed to the purpose of a change, do not understand their role in the change, or fail to engage on the necessary activities

- The delivery schedule for a change is unrealistic or a surprise, or efforts to deliver training and communications are late or incomplete

- Teams that were asked to complete important work for the change lack resources or skills

- The scope (i.e. expected outcomes) of the change is unclear, frequently changes, or grows significantly because of oversights

- Culturally, major parts of or the whole organization is locked-in to resist change due to unwritten rules, risk aversion, or structural disjointedness

When these issues lead to uneven change execution, the consequences can be serious:

|

Because of an inadequate understanding of change management, there is a tendency on the part of organization leaders to lump the above symptoms together, attribute them to people not doing as told, and label them resisters. However, structural disjointedness, poor planning, and inadequate resourcing are separate issues that have nothing to do with people's ability or willingness.

Of course, parts of an organization welcome the promise of working on change projects and reaping associated benefits. Almost always, however, there are people who resist. A nuanced approach is therefore necessary to understand how resistance works and what can be done about it.

Of course, parts of an organization welcome the promise of working on change projects and reaping associated benefits. Almost always, however, there are people who resist. A nuanced approach is therefore necessary to understand how resistance works and what can be done about it.

How Resistance Works

Imagine a scenario where a change project was perfectly scoped, planned, and delivered, but the new capability does not deliver anticipated benefits because people in the organization will not use it. Getting an organization ready for a change, accordingly, needs to focus on more than plans, schedules, and budgets. People's ability and willingness are critical factors, too. Some, however, will resist no matter how well the organization prepares.

What causes resistance? Most organizational change requires people to adapt routines and behaviors, adhere to new norms and values, and learn different skills. It also requires a mental shift to understand the change's purpose and accept that it is good for the organization. Mandating this belief rarely works.

Imagine a scenario where a change project was perfectly scoped, planned, and delivered, but the new capability does not deliver anticipated benefits because people in the organization will not use it. Getting an organization ready for a change, accordingly, needs to focus on more than plans, schedules, and budgets. People's ability and willingness are critical factors, too. Some, however, will resist no matter how well the organization prepares.

What causes resistance? Most organizational change requires people to adapt routines and behaviors, adhere to new norms and values, and learn different skills. It also requires a mental shift to understand the change's purpose and accept that it is good for the organization. Mandating this belief rarely works.

|

The central problem is that resistance is pre-programmed in humans. When we used to live in cages, survival meant being able to scan the environment for existential threats such as a hungry saber-toothed tiger. To defend or evade the danger, we had to become aware of it first. Today, our brain is still evolutionary programmed to sense variations in the environment, raise an alert, and take action. Even simple variances may be interpreted as uncertainty. Uncertainty, of course is the same as risk, and thus considered a hazard.

|

Changes in today's organizations are rarely of real danger and may merely involve deviations to what people know to be safe, familiar, or convenient. For example, having to learn a new IT system or being assigned to a different team. The brain, however, reflexively assesses variability as uncertainty and a threat to the self, which triggers an emotional response (fight, flight, freeze, or flock). These fear emotions compel the human organism to initiate measures so that it survives. It is our survival instinct that instigates autonomous responses.

The types of resistance seen in organizational change initiatives can be categorized as follows:

Resistance to change expressed through defensive or evasive behaviors isn't automatically bad. All behavior is data, which is why resistance can inform change management strategies. However, addressing the opposition only when it is already firmly established may result in further difficulties making a change stick. Good change management therefore warrants being proactive.

Change Leadership Strategies

Choosing the right strategies relies on a complete understanding of the departure point for the change journey, the organization's structure and culture, what resource capacities exist (people, processes, technology, funding), the intended outcomes and desired benefits of the change being pursued, and plausible reasons why the organization is (or is not) ready to accept the change.

The following strategies can be helpful to address resistance and enable adoption of a change:

Demonstrating future-state value, highlighting what will remain unchanged, providing an outlet (someone who listens), and giving people an opportunity to grieve their loss will be beneficial regardless into which of the above categories the majority of personnel targeted by a change fall. Unfortunately, some senior leaders expect that their staff should come on board with a change immediately, despite the fact that they themselves had weeks or months to think through it. Personnel should be given a suitable amount of time to do the same. The strategy of last resort, of course, may have to be to issue a decree or remove unbending staff. Positive outcomes, though, cannot be guaranteed when doing so.

What Else is Important?

Discrete funding and dedicated transition plans should be incorporated into project plans to assess readiness, involve staff, communicate frequently, and execute the change well. Enlisting those impacted by the change to help with execution can be beneficial since participation leads to commitment. At minimum, a dialog helps with creating acceptance when personnel feel heard, receive answers, and are part of determining the future state. Paying attention to resisters presenting an intellectual argument can be especially valuable. They care (why else engage?), can be converted into supporters, or may know of a solution to a problem that no one else thought of.

As for change communications, research has shown that staff members prefer to hear from senior leaders about vision/direction for the organization. Their supervisor is expected to address job responsibilities/performance and any changes happening in the organization. That is why engaging the middle of an organization system and enlisting a network of change champions can be effective. Communicating about change during times of uncertainty and ambiguity makes it immensely important that leadership actions are consistent with messages, which are delivered with credibility and empathy. For example, recognizing the hurdles that are ahead, how they could make the change difficult yet worthwhile, and how they could be addressed.

Measuring Change

Measuring change should take place in three areas:

Personnel sentiment can be assessed through surveys and by using change champions. Competency assessments should include talent, knowledge, suppliers, process maturity, and technology. Capacity constraints, on the other hand, need to be assessed in terms of funding, staffing, and time. Project outcomes can evaluated through key performance indicators, incl. sales performance and transactional or financial efficiency improvements. Measuring personnel engagement warrants enlisting support from Human Resources and using their assessment instruments.

Change Frameworks

Frequently there is too much attention given to project-planning aspects of a change initiative (i.e. tasks, milestones, schedules, budgets). Defaulting to project processes usually means that doing so is in the organization's comfort zone. It also could mean that it lacks the expertise to conduct organizational diagnosis. A grasp of the status quo (as expressed through culture, mission, norms, incentives, etc.), however, is usually helpful when embarking on a change.

The types of resistance seen in organizational change initiatives can be categorized as follows:

- Ideological: the individual believes (intellectually) that the change is the wrong thing to do, is doomed to fail, morally inappropriate, or will not work out as well as intended

- Political: the individual is convinced that they stand to lose one or many things valuable to them, for example position, power, perks, pay, or promotion

- Blind: the individual is irrationally opposed and may not be able to explain why they resist, perhaps out of fear, intolerance, or apathy

Resistance to change expressed through defensive or evasive behaviors isn't automatically bad. All behavior is data, which is why resistance can inform change management strategies. However, addressing the opposition only when it is already firmly established may result in further difficulties making a change stick. Good change management therefore warrants being proactive.

Change Leadership Strategies

Choosing the right strategies relies on a complete understanding of the departure point for the change journey, the organization's structure and culture, what resource capacities exist (people, processes, technology, funding), the intended outcomes and desired benefits of the change being pursued, and plausible reasons why the organization is (or is not) ready to accept the change.

The following strategies can be helpful to address resistance and enable adoption of a change:

- Ideological: Persuade convincingly, using as many facts and evidence as possible

- Political: Negotiate trade-offs/compromises and distinguish short/long-term impacts of the change

- Blind: Provide credible reassurances, allow more time to work through 'it', and create experiences that make the change real

Demonstrating future-state value, highlighting what will remain unchanged, providing an outlet (someone who listens), and giving people an opportunity to grieve their loss will be beneficial regardless into which of the above categories the majority of personnel targeted by a change fall. Unfortunately, some senior leaders expect that their staff should come on board with a change immediately, despite the fact that they themselves had weeks or months to think through it. Personnel should be given a suitable amount of time to do the same. The strategy of last resort, of course, may have to be to issue a decree or remove unbending staff. Positive outcomes, though, cannot be guaranteed when doing so.

What Else is Important?

Discrete funding and dedicated transition plans should be incorporated into project plans to assess readiness, involve staff, communicate frequently, and execute the change well. Enlisting those impacted by the change to help with execution can be beneficial since participation leads to commitment. At minimum, a dialog helps with creating acceptance when personnel feel heard, receive answers, and are part of determining the future state. Paying attention to resisters presenting an intellectual argument can be especially valuable. They care (why else engage?), can be converted into supporters, or may know of a solution to a problem that no one else thought of.

As for change communications, research has shown that staff members prefer to hear from senior leaders about vision/direction for the organization. Their supervisor is expected to address job responsibilities/performance and any changes happening in the organization. That is why engaging the middle of an organization system and enlisting a network of change champions can be effective. Communicating about change during times of uncertainty and ambiguity makes it immensely important that leadership actions are consistent with messages, which are delivered with credibility and empathy. For example, recognizing the hurdles that are ahead, how they could make the change difficult yet worthwhile, and how they could be addressed.

Measuring Change

Measuring change should take place in three areas:

- Pre-change readiness: assessing people's general sentiment about the change, and the organization's competency and capacity to deliver it

- The project's outcomes: evaluating benefits forecasts as documented in sponsor-approved business cases

- The impact on personnel: measuring engagement, participation, and motivation

Personnel sentiment can be assessed through surveys and by using change champions. Competency assessments should include talent, knowledge, suppliers, process maturity, and technology. Capacity constraints, on the other hand, need to be assessed in terms of funding, staffing, and time. Project outcomes can evaluated through key performance indicators, incl. sales performance and transactional or financial efficiency improvements. Measuring personnel engagement warrants enlisting support from Human Resources and using their assessment instruments.

Change Frameworks

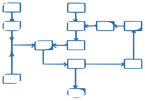

Frequently there is too much attention given to project-planning aspects of a change initiative (i.e. tasks, milestones, schedules, budgets). Defaulting to project processes usually means that doing so is in the organization's comfort zone. It also could mean that it lacks the expertise to conduct organizational diagnosis. A grasp of the status quo (as expressed through culture, mission, norms, incentives, etc.), however, is usually helpful when embarking on a change.

More comprehensive than 7-S, Burke-Litwin anchors in research on open systems theory and cell biology theory. These theories stipulate that:

An organizational assessment thus needs to develop insights about causality by taking a system-wide perspective of the organization, making sense of all its parts, and especially their relationships.

Ownership and Terminology

Making Human Resources (HR) or Information Technology (IT) accountable for change is sensible when its impact is limited to HR and IT. It makes less sense to compel either team to own enterprise-wide change. This remit would extend beyond these departments core competencies. Instead, HR and IT can be viewed as providers of expertise and solutions that change initiatives rely on, and a different department should be selected to own change management overall (more on this below). Additionally, ineffective management oversight paired with misjudgments about the intricacies of change can unnecessarily complicate execution. Most organizations correctly distinguish between project and operational work. However, maintaining effective oversight, correctly grasping the dynamics of change, and using terminology that everyone in the organization understands is where they can fall short. An example for the latter is when the terms transformation and change are used interchangeably.

But terminology confusion is merely a symptom. Above issues may be caused by the organization's tendency to artificially compartmentalize change projects as "true change" and "just another change we do". In this mindset, transformations are seen as valid change efforts with a defined scope/schedule that warrant dedicated teams to manage complex interactions. The other kind of change, it is assumed, can be handled alongside the regular workload. Three problems can result from this mentality. First, without effective governance, organization leaders are more likely to make unrealistic assumptions about capacity, capability, and efficiency. This first problem creates the second problem: contention over resources causing undisciplined shifts of capital and workforce commitments, which slows down execution. Third, selecting, prioritizing, and aligning the organization on change opportunities is challenging when there isn't agreement about what kind of work constitutes change.

To address these problems, organizations should decide where to designate a change management function, maintain an effective governance body, actively manage complexity, and agree to definitions that establish boundaries between business-as-usual operations and transformations. The right team to own enterprise-wide change management is Operations. Its mandate spans across the organizational matrix and the department is well positioned to sponsor a team with a composite skill set (HR and IT have the former but are too specialized for the latter). To clarify what kind of work constitutes change, the terms run-the-business (RTB) and change-the-business (CTB) can be adopted. Any work that is classified as RTB should not be treated as change. Within CTB, additional definitions can be used to classify and prioritize initiatives. Example definitions include value, ease of adoption, risk profile, required expertise, cultural implications, etc. One caveat: maintaining a governance function that oversees portfolios of change projects extends beyond traditional change management responsibilities into Project Portfolio Management, there are more ideas on this here.

- Organizations, their components, and relationships between components can be affected by the environment, can affect the environment, and may affect each other

- Similar to organisms, organization systems take from the environment, convert what was taken, and produce an output

An organizational assessment thus needs to develop insights about causality by taking a system-wide perspective of the organization, making sense of all its parts, and especially their relationships.

Ownership and Terminology

Making Human Resources (HR) or Information Technology (IT) accountable for change is sensible when its impact is limited to HR and IT. It makes less sense to compel either team to own enterprise-wide change. This remit would extend beyond these departments core competencies. Instead, HR and IT can be viewed as providers of expertise and solutions that change initiatives rely on, and a different department should be selected to own change management overall (more on this below). Additionally, ineffective management oversight paired with misjudgments about the intricacies of change can unnecessarily complicate execution. Most organizations correctly distinguish between project and operational work. However, maintaining effective oversight, correctly grasping the dynamics of change, and using terminology that everyone in the organization understands is where they can fall short. An example for the latter is when the terms transformation and change are used interchangeably.

But terminology confusion is merely a symptom. Above issues may be caused by the organization's tendency to artificially compartmentalize change projects as "true change" and "just another change we do". In this mindset, transformations are seen as valid change efforts with a defined scope/schedule that warrant dedicated teams to manage complex interactions. The other kind of change, it is assumed, can be handled alongside the regular workload. Three problems can result from this mentality. First, without effective governance, organization leaders are more likely to make unrealistic assumptions about capacity, capability, and efficiency. This first problem creates the second problem: contention over resources causing undisciplined shifts of capital and workforce commitments, which slows down execution. Third, selecting, prioritizing, and aligning the organization on change opportunities is challenging when there isn't agreement about what kind of work constitutes change.

To address these problems, organizations should decide where to designate a change management function, maintain an effective governance body, actively manage complexity, and agree to definitions that establish boundaries between business-as-usual operations and transformations. The right team to own enterprise-wide change management is Operations. Its mandate spans across the organizational matrix and the department is well positioned to sponsor a team with a composite skill set (HR and IT have the former but are too specialized for the latter). To clarify what kind of work constitutes change, the terms run-the-business (RTB) and change-the-business (CTB) can be adopted. Any work that is classified as RTB should not be treated as change. Within CTB, additional definitions can be used to classify and prioritize initiatives. Example definitions include value, ease of adoption, risk profile, required expertise, cultural implications, etc. One caveat: maintaining a governance function that oversees portfolios of change projects extends beyond traditional change management responsibilities into Project Portfolio Management, there are more ideas on this here.

|

Where to Start

A methodical approach to delivering change must not introduce bureaucracy and can be tailored to the organization's needs. To understand organizational change management maturity, the following areas should be evaluated: |

- History: reviewing execution approach and results of past change projects reveals lessons concerning the organization's approach on change management

- Expertise: whether configured as a centralized or decentralized team, experienced change practitioners engage sponsors and up-skill project teams to enhance organizational change management competencies

- Skills: best practices and procedural support enable staff who are not experienced change practitioners to develop the expertise necessary to perform according to their role in a change initiative

- Funding: a percentage of project budgets is dedicated to enable change planning, assessments, transitional activities, communications, and training

- Methods: change projects are planned and executed using industry-standard frameworks that were tailored to the organization's context and needs

- Adoption: as a common practice, effective strategies to sustain change are incorporated into project plans, are being measured, and adapted where necessary after the project closed

- Learning: post-deployment measurement and after-action reviews evaluate change initiatives to determine what worked well, where there are gaps, and whether projects deliver desired outcomes

- Culture: assessing the culture, including engagement, surfaces what may be causing inefficiencies when delivering change (e.g., silos, lack of trust, weak alignment, misunderstood mission, etc.)

It should not be expected that all challenges that surfaced during an assessment can be solved completely and immediately. In an organization that has difficulties delivering change, improving change competencies will be a change initiative in its own right. In most cases, identifying one major pain point and tackling that first is manageable and builds credibility. Ideally, improvements can be piloted within an area of the organization that is receptive to new ideas. From there, a further diffusion of the new change management approach can begin.

* * *

Change is messy and difficult. Frameworks and best practices help delivering change but only enable us to cope with uncertainty and manage through ambiguity. A skill that change practitioners (and organizations) can embrace to increase their capacity for change is learning agility. Once culturally embedded, renewal and advancement are less daunting. Delivering continuous change becomes part of the organization's fabric.

Reference: Burke & Noumair, Organizational Development; Pasmore, Leading Continuous Change